How to Test Your Cybersecurity Incident Response Plan

- Updated: June 19, 2025

- Read time: 4 mins.

In this article...

- Understand why incident response testing is essential.

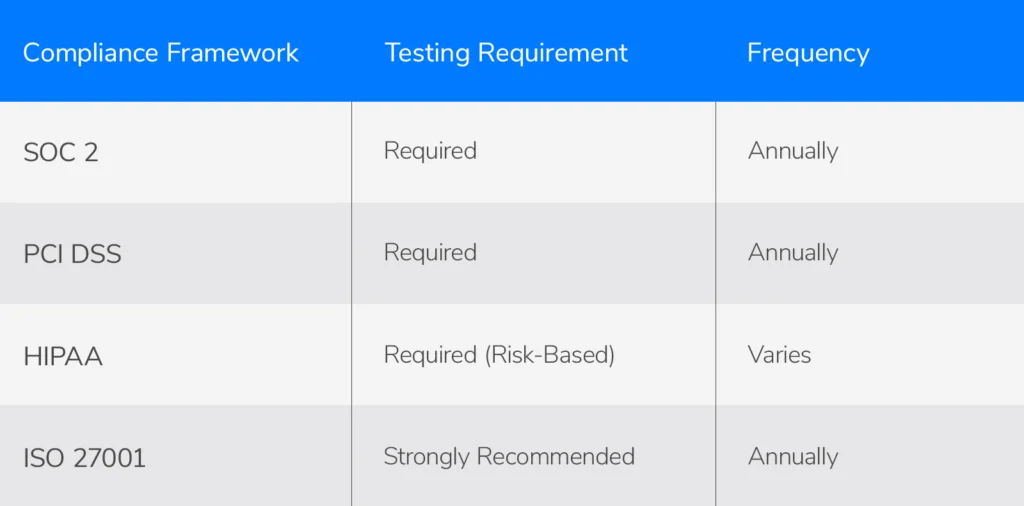

- How compliance frameworks like SOC 2 and PCI DSS influence your testing strategy.

- The difference between tabletop exercises, walkthroughs, and cutover simulations.

- Tips for choosing the right testing method for your cybersecurity maturity.

You care about protecting your organization’s operations—and you’ve written a solid incident response plan to do just that.

But here’s the real test: does your plan actually work?

As Mike Tyson famously said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” When a cybersecurity incident hits, things get chaotic fast. That’s why it’s critical to regularly test your cybersecurity incident response plan—and the people and technologies that bring it to life.

In this article, we’ll break down the three most common incident response testing methods, from tabletop discussions to full simulations. Whether you’re doing it to meet compliance standards or strengthen your real-world readiness, you’ll walk away with actionable insights.

How Do I Choose the Right Incident Response Testing Method?

You don’t have to wait for a breach—or even a compliance requirement—to test your plan. But if motivation is lacking, regulatory pressure might do the trick.

Frameworks like SOC 2, PCI DSS, ISO 27001, and HIPAA often require annual incident response testing. These standards rarely dictate how you test—but they do expect documented proof that you’ve done it. Depending on your risk profile, you might even test quarterly or semi-annually to stay sharp.

And it’s not just auditors who are watching. At HBS, we’ve seen large clients demand evidence of rigorous, recurring testing before signing vendor contracts. Some go as far as rejecting proposals if the incident response testing process doesn’t meet their expectations.

Choosing the right testing method comes down to three things:

- Your organization’s cybersecurity maturity

- Your risk tolerance

- Your compliance requirements

Let’s walk through your options—from theoretical to fully simulated.

Tabletop Exercise: A Basic Incident Response Plan Test

The tabletop exercise is the entry point for testing. It’s low-cost, low-risk—and still incredibly valuable.

Here’s how it works: you bring the core incident response team into a room and walk through one or more breach scenarios. Everyone talks through their responsibilities, referencing your documented plan.

Even this theoretical test can uncover major issues. Questions that often surface:

- “How long will it actually take to restore our data from backup?”

- “Where is the employee contact list stored—and what if that server is down?”

- “What’s our SLA? Are we confident we can meet it under pressure?”

- “What does this step even mean?”

These are red flags worth fixing—before an attacker finds them first.

TIP: Review real incidents like the Colonial Pipeline breach. They had a plan, paid the ransom, and still spent days restoring operations. Theory doesn’t always hold up under pressure.

Check out some sample tabletop exercise scenarios.

Walkthrough Test: Verifying Your Cybersecurity Plan in Action

A walkthrough test brings your plan out of the binder and into the building.

You’ll follow each step of your incident response plan as if a real event were unfolding—without actually triggering technical actions like failovers or restorations.

Common walkthrough activities include:

- Calling the contacts listed in your plan to verify they answer in time

- Sending test alerts and emails (clearly marked as tests)

- Walking the floor to confirm critical staff are where they’re supposed to be

- Checking how long specific tasks actually take in real life

Don’t forget the HR and communication angles:

- Will people on PTO respond to alerts?

- If operations halt, do employees go home? Do they still get paid?

- Are expectations clear for remote workers

Walkthroughs shine a light on the human side of cybersecurity incident response. Plans that look solid on paper often falter when put into motion.

Cutover Test: Full Simulation of Your Incident Response Plan

Ready for the real thing? A cutover test is the ultimate simulation.

In a cutover, your team executes the plan as if a breach has already occurred. You might simulate a total failover to cloud systems or force a generator startup by killing the power (yes, some organizations really do this—with planning and care).

These tests validate what actually works—and what doesn’t:

- Does the alternate system launch as expected?

- Can you restore data from backup fast enough?

- Are people trained to execute their parts under pressure?

Cutovers are demanding. They create real downtime, require significant coordination, and may even prompt you to rethink vendor contracts if the test requirements outweigh the business benefit.

WARNING: Never cut over all systems at once. Targeted simulations reduce risk while delivering insights.

Incident Response Compliance Requirements to Consider

If your organization handles sensitive data or operates in regulated industries, compliance-driven incident response testing may not be optional.

No matter the framework, auditors want to see:

- Documented test procedures

- Clear test results

- Evidence of lessons learned and updates to the plan

Why Use a Third Party for Incident Response Plan Testing?

Whether you’re running a tabletop, walkthrough, or cutover, a third-party facilitator can help you spot weaknesses you might miss.

A qualified advisor brings two things:

- An outside perspective rooted in cybersecurity best practices

- Deep experience across industries and incident types

"One side knows the business, and one side knows incident response planning. You want to marry those two to manage that responsibility."

-Jeff Franklin, HBS Senior Information Security Consultant

Even if you hire outside help, your team should still lead the test. This builds hands-on experience and strengthens your response muscle memory.

Final Thoughts: How to Test an Incident Response Plan That Actually Works

Testing your incident response plan isn’t just a checkbox. It’s a strategic investment in your organization’s resilience.

Start with a tabletop, move to a walkthrough, and consider a cutover when you’re ready. Each method increases realism—and your ability to confidently respond when it counts.

Need help selecting the right approach or running your next simulation?

Contact HBS to talk with our cybersecurity advisors.

Related Content

Incident Response Tabletop Exercise and Scenarios

Enhance your cybersecurity with our realistic tabletop exercises. Practice incident response and identify plan changes with our sample scenarios.

How to Conduct an Effective Tabletop Exercise

Discover tips for running a tabletop exercise that effectively tests your incident response plan and prepares your team for a real breach.

Creating an Incident Response Plan

Creating an incident response plan is critical for the stability of any organization, and setting one up does not have to be stressful with these tips.